|

Visit to Gallipoli - Turkey One of the greater battles of World War One was situated in Turkey on the Gallipoli peninsula overlooking the Dardanelles. This campaign also signifies a national holiday in Australia and New Zealand called Anzac Day. The allied objective of the Gallipoli campaign was to force Turkey out of the war and to secure an ice-free sea supply route to Russia to open another front against German and Austria-Hungary. Four countries took part in the landings, Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand with the last two a joint force called the Anzacs (Australia New Zealand Army Corp). On the 25th of April 1915 the Anzacs landed at what is now called Anzac Cove on the western side of the Gallipoli peninsula - at the wrong point due to currents over night. Over the next nine months this disastrous campaign fought on and on with the loss of more than 36,0001 allied soldiers and 85,000 Turkish soldiers. In the end the allies withdrew to avoid further losses and the Turks celebrated their victory. Of the 8,556 New Zealand soldiers that landed 7,447 were killed or seriously wounded in the battle. The importance of this battle to New Zealand history made this an important part of my trip to Turkey. . . Riding down the Gallipoli peninsula I was apprehensive about visiting these ancient battlefields that since childhood we have remembered every 25th of April on Anzac day. Gallipoli always held a compelling yet distant allure for me. So much history and so much bloodshed that turned out to be needless. Would it still be such an important event in our history if we had won? Images assaulted my mind from the history books and films I had seen on the even. I am curious in a morbid way as to what it would all look like.

We keep riding, looking at our maps which do not provide us enough detail as to when to stop. Finally we pull to the side of the road where a fruit stand sites in the warm afternoon sun. I approach the fruit seller and ask whether he speaks English. Shading his eyes against the sun he shakes his head and mumbles in Turkish. Undeterred, I plead "Anzac Cove" in the clearest English I can muster. With an energy I couldn't guess where it came from, he sprang towards me with his hand outstretched. "Anzacs - Australian?" he asks? Relieved I nod - "New Zealand"

Before me, again, I am seeing pictures of trenches, monuments, graves and old pictures of soldiers. Seeing the images is different than before, as they are pictures of the mountains and seas just around me. I nod to each of his explanations and he finally runs out of breath. "Map?" I ask. Understanding he points to one particular page where a map of the peninsular lies before me. It's the same as our maps and doesn't provide the answer we are looking for. "Where is Anzac cove" I request hoping he can understand my words. He does and points further down the road then motioning right. 2 and 12 km he writes down on a paper in front of me. I think I understand. Two kilometers ahead there is a side road where 12 km further takes us Anzac Cove, the Museum and the Cemeteries. Gratefully I thank him, pat the dog at his feet and accept the two walnuts eagerly pressed into my hands. He waves good bye as we start our bikes and continue on our way as I wonder how many times he does this each day. Just around the corner we easily spot the turnoff. English and Turkish signs announce the way and the distances. Around us the air is still and quiet with only the bark of a dog in the distance. The occasional farm tractor noisily drives by showing that not much happens down here anymore apart from farming. All the hills are brown and dry with few trees. It doesn't feel like summer nor does it feel cool enough to be winter.

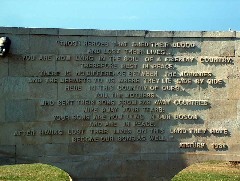

I ignore the appeals for purchase and dismount from my bike and take a look around me. The museum is a modern structure surrounded by plaques, statues and various other types of structures paying homage to the past. I stop halfway up the steps and question my being here. Would it have been better to just leave this as one of those places on the other side of the world and in the history books? Almost as if to answer me, a tablet to my right catches my attention and I turn to read it. It finishes with the words:

The exhibition consist entirely of articles from the period starting with the tools used to dig the trenches, then proceeding to small seemingly insignificant possessions they carried such as lights, plates, forks and compasses. Time has made them all far from trivial though with the rust, aged look and the occasional object with a bullet hole in it. Photos on the wall depict an allied soldier helping a wounded Turkish soldier, a soldier carrying a wounded comrade on the back of a donkey, a group of New Zealand soldiers looking solemnly into the camera while smoking a cigarette. They start to blur into each other while each individually becoming burned into my mind.

I need to get out. Bolting for the exit, I breath the gentle breeze of dread and regret. Outside, I persist and wander the various shrines commemorating the deeds and characters of the various soldiers from the battles. Interestingly enough there is an equal mixture between the memorials for the Turks and the invaders as they so put it. It's interesting that both parties are treated with equal respect by the builders - a sure sign that forgiveness is as solid as the walls surrounding the museum. Once Matt and Ilja are ready we mount the bikes once more and head off to Anzac Cove itself about 6 kilometers down the way.

A fitting tribute and sign of the strength of the Turks in forgiveness.

We spend the next couple of hours silently viewing the cemeteries that litter the hills above. Thousands of graves that are still unsure whether they belong in that particular area fill the senses to the total loss of life that was endured during those eight months. Reconstructed trenches run throughout these rises some as little as 4 meters from each other illustrating just how close the fighting was. Finally, we must move on before the sun drops to low for us to find our way and we depart to Troy the scene of another battle that took place thousands of years before just 50km away across the straight. I ponder over the next few days the significance of my visit to Gallipoli but still cannot come to an explanation of why it was such a forceful and emotional experience for me. I can only leave with the fact that I was glad that I had visited. Shaun - 13th October 2003

|